Hey, Squirrel! There's an Owl in Your Digs

By Hans Bertsch

It's

protective: prairie dogs stand alert, gophers buck-teeth a

peek, and ground squirrels skitter down with tails a-swish. But

an owl hooting underground from a burrowed home? Well, shake

your wings, bob your swiveling head, and blink those big yellow

eyes!

It's

protective: prairie dogs stand alert, gophers buck-teeth a

peek, and ground squirrels skitter down with tails a-swish. But

an owl hooting underground from a burrowed home? Well, shake

your wings, bob your swiveling head, and blink those big yellow

eyes!

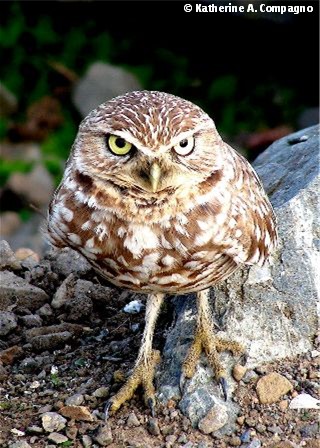

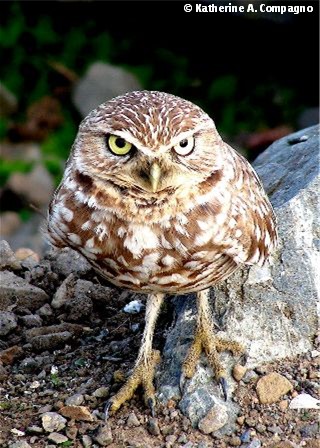

You are a burrowing owl, lechuza de tierra,

buho pigmeo, or scientifically Athene cunicularia.

These sociable owls are a real

hoot, popping in and out of their commandeered burrows, cranking

their heads sideways while sitting on fence posts, and

scampering through air or scrubland to eat little mice, insects,

or the occasional frog or small bird. Especially enjoyed

insects are the juicy, water-rich grasshoppers, crickets and

beetles. They often nest in colonies, in the abandoned burrows

of not just ground squirrels and prairie dogs, but sometimes of

skunks, badgers, Texan armadillos, black chuckwallas, and even

Gopherus desert tortoises. Their scientific name is

from the Latin for “underground passage dweller,” or “miner.”

Burrowing owls occur in treeless

open grasslands and desert scrub throughout the western U.S.,

Mexico, Central and South America, and Florida and the West

Indies. Specimens have been found in various Pleistocene

deposits within that range.

First reports of burrowing owls

in Baja California (by S. F. Baird, 1874) were from the Cape

Region. We now know this species is widely distributed along

the low-lying sides of the entire peninsula, most commonly in

the northern and central regions. These landlubbers have also

been sighted on 23 islands, including most of the coastal

Pacific ones. In the Sea of Cortez, they have been reported as

“vagrant” (nonresident) on a dozen islands. They have even been

seen on little Isla Piojo at Bahía de los Ángeles. Although one

wouldn't consider burrowing owls to be marine birds,

investigators on board ships have watched them flying over water

to the islands.

Human activities seem to have

affected both their habitat abundance and population decline.

Eduardo Palacios and his colleagues reported (Western Birds,

2000) that in the peninsula, 43% of the species' sightings were

in agricultural lands (reflecting the abundant coastal farms and

human habitat use), and 18% in wetlands, 15% in the open desert,

and 12% in coastal sage scrub. At the same time “other human

activities such as poisoning and loss of nest sites through the

control of squirrels and prairie dogs” have diminished their

numbers to the point of being a “species at risk” in both the

United States and Mexico.

The bird stands 8–10 ½ inches

tall, with a wingspan of about 22 inches. Most owls have short

legs, but because of its terrestrial habits, these owls have

evolved much longer legs. They seem to have the most furrowed

brow of all owls—maybe in the vein of the High Plains Drifter

Clint-squint. A black eye crest often droops halfway over the

eye, and its white chin contrasts the black neck ring. Its

chest is whitish to mottled soft brown, and the brown

white-speckled wings vary in darkness throughout its range.

Its Athene relatives, the

Eurasian little owl (A. noctua) and the spotted owlet (A.

brama) of the Middle East, India and Indo-China, are forest

adapted, nocturnal owls, with more owl-typical shorter legs and

headlight eyes. The genus name is the Greek goddess of wisdom

and the arts, perhaps based on an equally legendary wise ole

owl.

Kids are definitely a family

affair. The clutch of 5–12 eggs is incubated for about 4 weeks

by both mom and pop, who also share in the feeding, training and

teen-age controlling. Spring and summer time at the Burrow

Owls' digs is a whirligig of practice fluttering and running.

They can imitate the “buzz” of a rattlesnake to frighten off

predators. However, a winged shadow passing across their

playground causes an immediate dive into their fortified

Predator Shelter. After a quiet lull, assured the danger has

passed, they all scurry topside to continue their 40 days of

lessons in growing up.

Life is a grand cabaret of

survival skills and antics: the “yawn” preceding their

regurgitation of undigestible bones and fur (swallowed whole,

the hard parts of prey are collected in a gizzard to be coughed

up as a casting), preening feathers from their oil gland near

the base of the tail, or just a sideways glancing “Here's at

you!”

So, ground squirrels, look out.

There could be a lady burrowing owl watching you now, waiting to

take over your digs. These buhos are definitely good

neighbors. They eat agri-pests, serve their ecosystem well, and

are fun to observe. They are definitely not Shakespeare's

“fatal bellman which gives the sterns't good-night.” They seem

to be quite happy sprites. Say their name out loud several

times:

¡Buho! ¡Buho!

and you will hear their gleeful

call. Maybe their burrowed lives are paraphrasing John

Steinbeck's excuse-to-do-science:

“Here was life from which we

borrowed life and excitement. We do these things because it

is pleasant to do them.”

It's

protective: prairie dogs stand alert, gophers buck-teeth a

peek, and ground squirrels skitter down with tails a-swish. But

an owl hooting underground from a burrowed home? Well, shake

your wings, bob your swiveling head, and blink those big yellow

eyes!

It's

protective: prairie dogs stand alert, gophers buck-teeth a

peek, and ground squirrels skitter down with tails a-swish. But

an owl hooting underground from a burrowed home? Well, shake

your wings, bob your swiveling head, and blink those big yellow

eyes!